What is Reverence for Life?

Swimming with my eight-year-old daughter requires patience. Actually, she’s pretty much a mermaid and can swim circles around anything just shy of a dolphin. But when the sun starts turning your skin oh-so-crispy bacon and your fingertips begin to resemble wrinkly raisins, she’s ready to devote another hour-plus in the pool, not to butterfly strokes, but to rescuing ants and bees and other creepy-crawlies that have fallen hapless victim to the water.

My daughter is amphibian in her devotion to preserving life. The other night, in the dry confines of our living room, she lectured me following my “coldblooded murder” of a centipede that I caught trespassing across our carpet. Her earnest chiding caused me to consider my thoughtless act of centi-cide. Later that evening, my daughter asleep, I redeemed myself. Another many-legged arthropod reared its forcipules; this time I captured it with a napkin and released it into the untamed wilderness beyond my porch door.

These days, I can hardly get away with swatting a mosquito in my daughter’s presence. Yet I have no one other than myself to blame. I’m the one who taught her Reverence for Life.

My daughter isn’t naïve about this way of thinking. (That is how I define philosophy to her: a way of thinking.) She understands that not all life is destined for tranquil retirement in the Florida Keys. She knows that humans are often compelled to terminate life for defensive and sustenance purposes. She also is aware that our bodies are self-contained Cosmoses of Life—that our very existence depends on billions of microorganisms within and upon us, yet that our bodies wage a constant war against microbes that would do us harm. Still, my daughter enjoys corndogs and pepperoni pizza as much as any other second grader—whilst wondering aloud from time to time what life as a vegetarian might be like.

While my daughter’s developing brain might not be truly capable of understanding that all life is a genetic wonder house, she knows that life qua life means more than all the bits and baubles in the world. (This coming from a girl who started her own school cafeteria beading enterprise—she knows the value of a quality bit and bauble.) And here is where she draws the Reverence for Life line: he who squishes a centipede for no good reason is guilty of barbarism.

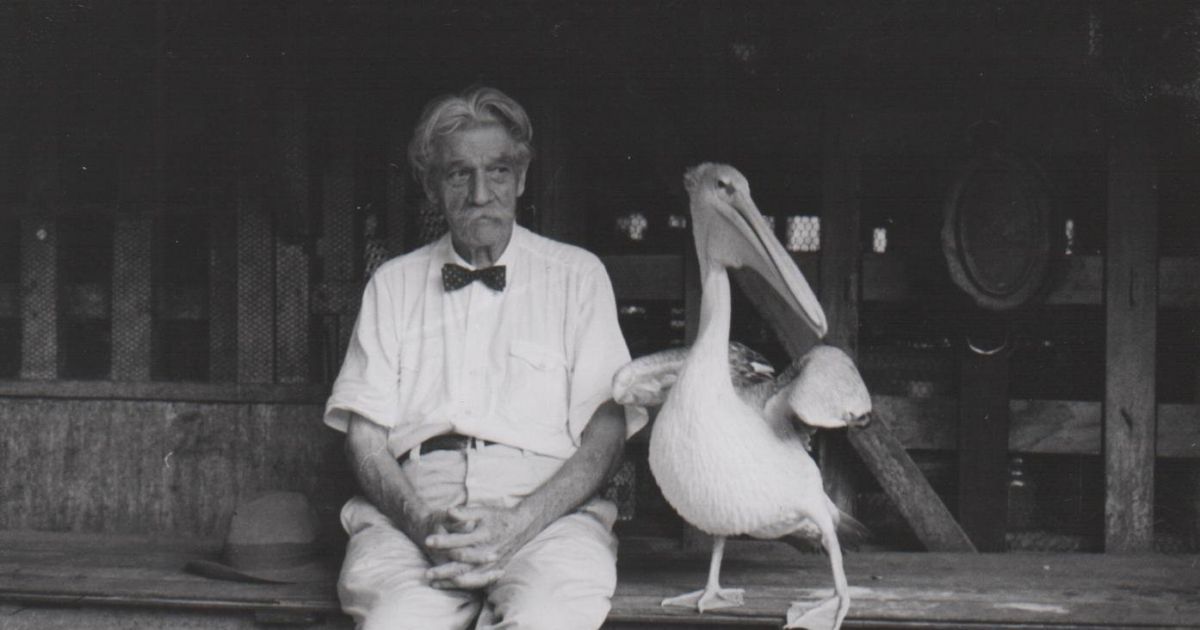

I’m grateful my little life-revering apprentice is there to catch me when I fall short of the glory of Albert Schweitzer. Yet I’m hardly an unredeemable barbarian. Not even Schweitzer had all the answers: in order to feed his sick pelican, he had to kill a fish. That’s what I tell myself every time I drop a half-pound of diced bacon into a mixing bowl of mashed potatoes, or empty a can of Lysol about the house after my Norwegian Forest cat, Thor, unloads a litter box bomb.

This is the dynamic of Schweitzer’s philosophy at work in the souls of a dad and daughter in one humble home. Reverence for Life has had a global impact as well: Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring, which spawned the environmental movement, was dedicated to Albert Schweitzer.

What, then, is this way of thinking called Reverence for Life?

Anyone who wants to embark on a serious study of the philosophy should begin by reading Schweitzer’s essay, “The Ethics of Reverence for Life,” which was first published in a 1936 issue of Christendom. (The article is available at the above link on the Chapman University website.) The text is intentionally heady at times, with nods to great thinkers like Spinoza and Hegel and Fichte. After all, Schweitzer had spent an entire academic career contemplating the question: “What is Civilization?” This essay is his intellectual response.

Schweitzer also approved of a much more practical foundation. He stated in Out of My Life and Thought that Reverence for Life begins with the awareness that “I am life that wills to live in the midst of life that wills to live.”

Simple enough, right? Yet it’s one thing to believe that life is a Darwinian, all-you-can-eat buffet, and quite another to build an evolving knowledge base, as I have attempted to do for my daughter, that demonstrates one’s place in the epic expanse of Life on Earth.

But mere awareness cannot build Civilization. One must ultimately act—and in the case of Reverence for Life, act with ethical reverence:

Ethics is nothing other than Reverence for Life. Reverence for Life affords me my fundamental principle of morality, namely, that good consists in maintaining, assisting and enhancing life, and to destroy, to harm or to hinder life is evil. (Albert Schweitzer, Civilization & Ethics)

And that, dear reader, is all one needs to begin. If there’s one thing I’ve discovered on my Reverence for Life journey, it’s that each individual must learn for himself or herself the difference between “good” and “evil” as Schweitzer defined it. Before the day is done, you will have unwittingly destroyed millions of microorganisms, eaten a chicken or pig, yet perhaps saved a pooch from the pound, plus showed kindness to a stranger that played forward positively in ways you never could have imagined. The difference now, perhaps, is that you may never have considered how your own life so constantly intersects with other life in a make or break manner.

Daily contemplation and devotion to the wonder of life—considering how every archaea, protist, fungus, bacterium, plant and animal is by itself as glorious as an entire galaxy of stars—ultimately will guide you on your daily Reverence for Life path.

By the way, I asked my daughter for her own definition of Reverence for Life. She thought about it and replied, “Just taking one life or saving one life matters to all the life around it.”

I like it: a metaphysical butterfly effect. Albert Schweitzer and his pelican surely would approve.

…

(Photo credit: Archives A. Schweitzer Gunsbach)

…

- Posted by

Arik Bjorn

Arik Bjorn - Posted in Arik's Blog

Dec, 01, 2015

Dec, 01, 2015 No Comments.

No Comments.

I think Uber Nights is the perfect bathroom book. If there are any public libraries out there listening, I think they should put a copy in every stall.

-Read more about Uber Nights